“The forces of evolution act upon a man’s tools as well as upon man himself “

A.C. Littleton (1926, P.12)

Welcome to the tale of an Accounting Academic who transformed into an Accounting Technologist, Accounting Historian, Accounting Anthropologist and a pretty decent knitter…

Dr. Lesley Niezynski is an early career interdisciplinary accounting researcher specialising in accounting technology, history and humanity. Lesley’s research centres on the interconnectivity between accounting, humanity, and technology.

Lesley has recently completed her PhD, a project centred upon the interconnectivity between humanity, accounting and technology through a study of Maritime Technology, Accounting and Merchants in Early Modern England.

Prior to accounting, Lesley’s interest in boundary blurring, human-centric research formed in her studies in Architecture, with studies in the interconnectivity of Architecture, Fashion, and Health.

What is she up to right at this very moment? Find out here.

I’m now on Substack! Find me at https://accountingforhumanity.substack.com/

-

2022: The lessons I learned from a pile of books

This is not likely to be my final post of the year however, pre-Christmas felt like a natural point for partaking in some good old reflection to give some direction for my 2023 goals.

2022 in 8 Books

Resolutions and reflections are processes that have been a near constant part of my mental space throughout my life although, it has admittedly not been a space that has seen much success. In recent years however, I seem to have found myself able to learn some valuable lessons from these processes and even celebrate some small successes in my goal setting.

In 2022 this all derived from a simple New Year’s Resolution. In my ambition to ‘read more books’, I have learned some invaluable lessons that I have been able to successfully transfer into my PhD studies/research and witness some very welcome progress.

So, what did I learn from reading more in 2022?

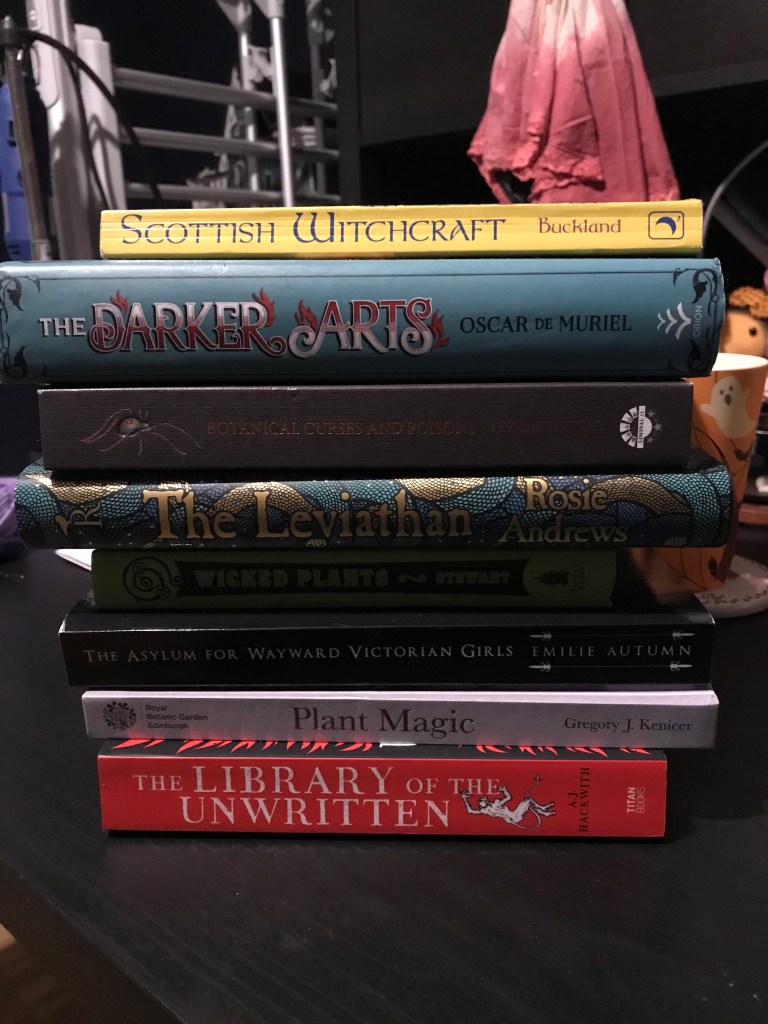

I have too many unread books…

The purpose of the resolution was to get back into reading for leisure. In 2021 my reading rate was what could be described as ‘diabolically slow’ for someone in possession of a mountain of unread books. I have the problem of possessing more ‘unread’ than ‘read’ books, and this is something that I was/am absolute in my determination to amend.

While having an undoubtedly huge task ahead (as mentioned, I possess many, many unread books), I entered this resolution not with the priority to read until my eyes bled, but with the want to experience a ‘win’ in resolution making. I was not prepared to see this go the way of many a New Year’s Resolutions i.e., admitting defeat by February, I wanted the joy of feeling accomplished, I wanted the ‘win’. I am unsure of what prompted this approach but, it was most definitely an unknown experience for me. I am known for pushing myself too far, burning out, and deriding myself over having burned out before meeting my target. Yet, here, I was placing myself and happiness first and was subsequently pleasantly surprised to feel that, even before setting the target, I was already feeling good about the journey to meeting this goal.

Lesson 1: It is about the winning, not taking part

Hear me out, this is not about throwing caution to the wind and doing whatever it takes to ‘one-up’ competitors to win recognition; this is about positioning yourself in the right space to enjoy the experience that you are about to partake in. Thus, it is not strictly about ‘winning’ something in the sense of being 1st place or being ‘the best’, it is about going into something with the feeling that you have already achieved something incredible. It does lie close to the ‘Positive mental attitude’ cliché but, there is merit in embracing in the positivity that comes with acting like you have already won. It brings a level of confidence (note: confidence, not arrogance) that can birth and maintain the motivation needed to make the most of experiences and achieve your goals.

Bringing this into the PhD context, the lesson here for me is creating plans and targets that will bring enjoyment to my studies. The ‘real’ goal becomes about enjoying the journey; the ‘targets’ are just different waypoints, markers, and rewards to keep that enjoyment going. I used applied this lesson in 2022 to help me focus on my writing, at the beginning of the year I began worrying excessively about not knowing what direction my thesis should take, a worry that inevitably caused progress to stagnate. Changing my focus from thinking about the final ‘big’ goal (i.e., a completed PhD thesis) to writing about a subject that I enjoy, allowed me to work past those writing ‘blocks’ and now at the end of 2022 I have created a healthy supply of content that I can now use to create a literature review.

Lesson 2: Being ‘Realistic’ is not about Letting go of your dreams

To be ‘realistic’ is generally accompanied by negative connotations however, there is more to it than ‘letting go of your dreams’, ‘giving up’ or ‘settling for the next best thing’. Realism for me is the opposite of giving up, being ‘realistic’ is about finding the path that ensures that I will reach my goals, whether that involves taking obstacles ‘head on’, or finding another, longer way around.

It has taken many years of counselling and therapy but, I have finally learned how my mind works in the realm of achieving success. I know when I can push myself that little bit farther, when I am near my limit and, most importantly, when I have pushed too far. This for me is realism. It is about knowing oneself and understanding that one size most certainly does not fit all. My experience is not the same as yours, we may face similar challenges but, they will never be the same. In addressing ‘being realistic’ I have learned that, for the most part, I am a creative problem solver thus, I am more akin to the ‘find a way around’ an obstacle kind of individual.

In terms of applying this to my reading resolution, I wanted this reading quest to be more that a ‘one-off’. The aim was to install a new long-term habit and thus, I had to create a sustainable or ‘realistic’ goal. At first, I thought of reading one book per month but, considering I had read around 3 books in the entire 12 months previous; I suspected that this would be a step too far i.e., not realistic. Furthermore, in addition to considering the prior lesson about aiming to create ‘little wins’, reading is supposed to be fun and as such, pressurising it was not going to make it fun.

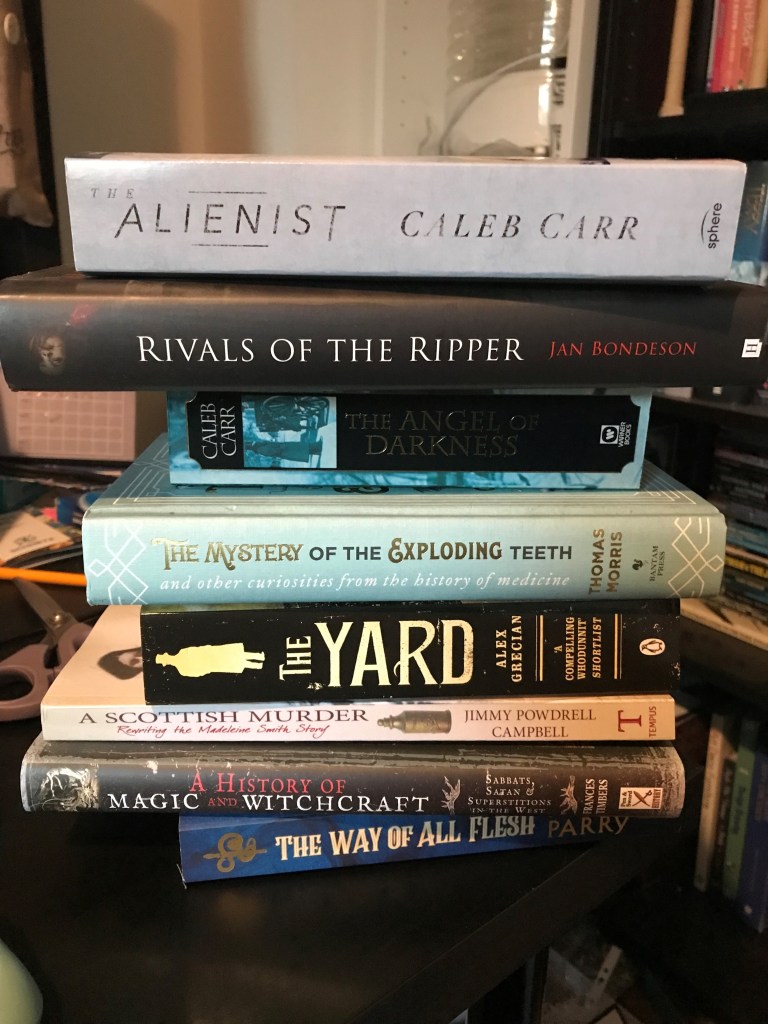

While the aim was to make this goal attainable I did, however, still have to make this a challenge. Thus, I needed a ‘balanced’ challenge; 75% effort, 100% of the time would be worth more to me in the end than a crazed 110% effort for 2 months followed by 10 months of burnout. With these parameters considered, I opted for 8 books in 12 months (1 around every 1.5 months). Additionally, I knew I had to vary my reading. I read fiction reasonably quickly, but non-fiction can take longer thus, to avoid frustration or stagnation, I would read 1 fiction followed by 1 non-fiction and carry on in that pattern.

This ‘realistic-inspired’ approach was exceptionally useful in my PhD research and writing as it allowed me to become more adaptable in my working methods. I learned to recognise days where my motivation was lower and thus, focus my goal for the day to suit my mood. My days now alternate between reading-focused, reading/summary writing and writing focused and I will dedicate an average of 1-3 hours on my thesis (1-2 hours being most common). With this variety and knowledge of my limitations, I have been able to maintain a productive pace throughout the entire year, something I was unable to do the previous year (2021 ended on 5 months of limited to no-PhD work and panic). As a result, being ‘realistic’ has brought me far closer to my PhD goals than my overly ambitious approach in 2021.

So, how did I do with my ‘Reading Resolution’?

Well as you may have guessed, the reason for writing this post was because I did complete my resolution (though I would have still written it if I had not succeeded as lessons still would have been learned). I read all 8 of my pre-selected books plus 3 more (and 2 additional theory books for my thesis). The motivation for this is not to brag, yes it feels good to be able to say what I have achieved and I am proud of myself but, my compulsion to share is based more on my feeling that what I have learned from this experience is extremely valuable.

I fully expected to encounter exceptional difficulty in attempting to read these books while also working on my thesis, reading all the thesis literature, and continuing in all the other activities that I enjoy. I thought incorporating reading into my routine would mean the loss of another activity (I think there is also a lesson here in identifying ‘idle’ time, as I may have more of it than I claim). I had hoped to reinstate a past hobby and create an ‘escape’ from my thesis (while I enjoy it, it is important to ‘pull’ my mind away from it sometimes) but I did not expect to emerge from this year having learned such valuable lessons in planning my PhD research. This simple resolution allowed me to reframe my mindset in approaching my work, the once impossibly high bar now rests a little lower, if not replaced entirely by a series of smaller hurdles, each one easily traversed in consistent little leaps and bounds.

Who knew you could learn so much from reading a book…

Yes it appears that I have a theme when it comes to my reading…Victorian crime anyone?

Follow me on Bluesky

@lniezynski.bsky.social